The Canadian government recently introduced Bill C-69, claiming that this legislation delivers on a campaign promise to “restore lost protections, and incorporate more modern safeguards” in several environmental statutes. While media reports focused on changes to environmental assessment and energy law, the Bill also includes major amendments to the Navigation Protection Act – to be renamed the Canadian Navigable Waters Act.

This post looks at those amendments, which in my view fail to live up to the government’s promises. More needs to be done to restore lost legal protections related to navigable waters.

The rollback of Canada’s navigable water protection

Prior to 2012, Canada’s environmental laws clearly required environmental impacts to be considered – even if only briefly – before the federal government would approve development on navigable waters. The requirement that the government consider environmental impacts in decisions concerning navigation was eliminated in Bill C-38, through amendments to the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act.

Later in 2012, Bill C-45 limited the requirement for the federal government to approve development on navigable waters, so that it only applied to the rivers, lakes and oceans that appear on a list or schedule – which initially included just 159 rivers and lakes (plus three oceans). This was a loss of key legal protections for the vast majority of Canada’s estimated 2.5 million navigable rivers and lakes. The changes that created the current Navigation Protection Act were strongly criticized by the opposition parties (including the now governing Liberal Party of Canada), as well as environmental organizations, the Idle No More movement and recreational boaters.

Do the new Bill C-69 amendments restore lost legal protections? Unfortunately, no. The restored legal protections are narrowly focused, exclude environmental values, and in many cases are substantially weaker than the pre-2012 version of the law.

New law: navigation only or environmental values too?

Call it a clash of world views: Are Canada’s lakes and rivers and oceans a highway for transportation? Or are they, as Canada’s current Science Minister Kirsty Duncan put it in 2012, the “foundation of life … essential for socio-economic systems and healthy ecosystems”? Should the Canadian Navigable Waters Act only protect human navigation, or should it protect broader environmental, social and cultural values associated with navigable waters?

Canada’s newly unveiled Canadian Navigable Waters Act comes down solidly on the side of protecting what Transport Canada staff have called “aqueous highways,” rather than broader values.

Bill C-69 (both in the part about navigable waters and in the part related to impact assessments) does not restore the requirement to consider environmental impacts resulting from works in navigable waters (except in relation to truly huge projects that trigger an impact assessment).

Moreover, a narrower focus on navigation shows up right in the Act’s definition of “navigable waters.” While the courts have defined navigable waters as including any river or lake that is deep enough to float a boat, the new definition would only include rivers and lakes that are actually or “reasonably likely” to be used for commercial, recreational or Indigenous navigation and where currently:

- there is public access (including by navigating along a river or other water body);

- there are multiple owners of the land along the river or lake; or

- the federal or provincial government is the owner of lands along the water body.

This definition raises questions about whether the new Act will fully protect navigation for scientific, educational or other purposes (although we expect that the courts would interpret commercial and recreational uses broadly).

For lakes and navigable stretches of rivers that are surrounded by private land owned by a single owner, this definition:

- ignores environmental benefits of healthy water systems;

- ignores the heritage values of such lakes and rivers, where future landowners or ownership arrangements may give public access or result in multiple owners;

- creates a strong incentive for landowners to deny or challenge public access;

- fails to recognize the possibility of legal Indigenous access across private land.

These are not hypothetical problems. We’ve written about a large company suing a fish and game club rather than admitting that a public right of way exists for access to two lakes.

This narrower definition means that a significant number of lakes and rivers that had legal protection before 2012 will not get it back in 2018.

Later sections of the Act clarify that the Minister’s considerations in making decisions are focused on navigation. While we expect that the courts, based on historic decisions, will interpret “navigation” broadly as including environmental amenities, the government’s intent appears to be to limit the scope of the act.

One note of hope: the Act does require decision-makers to consider the impact of a decision on “the protection provided for the rights of the Indigenous peoples of Canada...” Consequently, in some cases where an Indigenous nation’s rights require consideration of the broader environmental, social and cultural values of a water body, the government may end up having to abandon its narrow “aqueous highway” approach.

What do you think? Do you agree with a narrow focus on navigable waters as highways? Or do you feel that decisions under this Act should consider the broader ecological and social values associated with Canada’s lakes and rivers? Tell us in the comments below (or better yet, tell your MP).

Limited scope of proposed new law

Further in the Canadian Navigable Waters Protection Act the government proposes to give some legal protection to all lakes and rivers that meet the new definition of navigable waters. However, the new legal protection is different, and often less than, than the pre-2012 provisions.

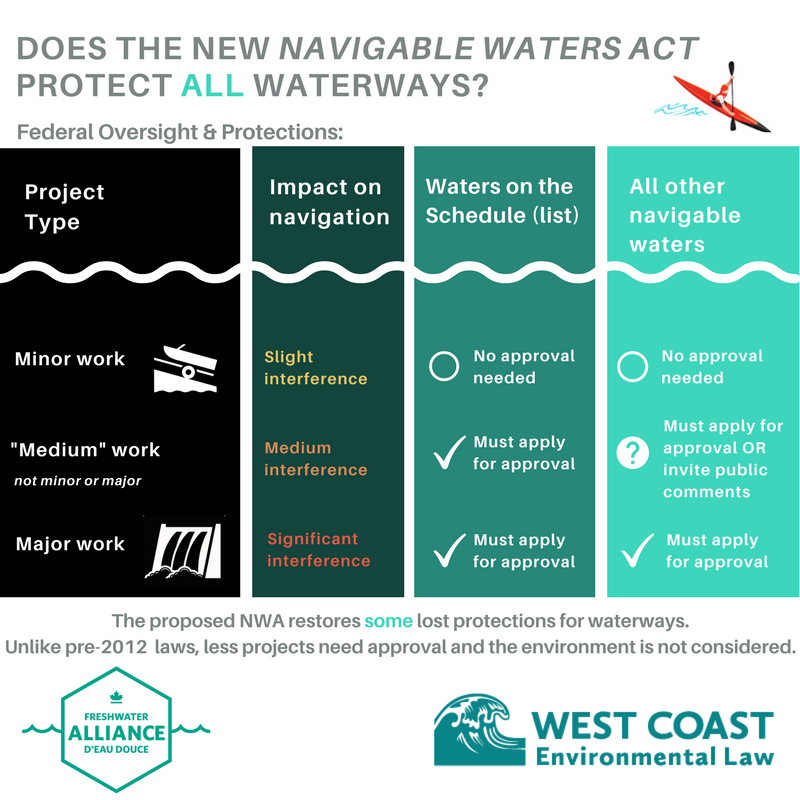

The new Act keeps the controversial “schedule” of navigable waters that the government considers particularly important from a navigation point of view (the 159 protected lakes and rivers). However, it also defines three categories of development that may take place on a river or lake: minor works, major works, and works which are neither minor nor major. The approvals a developer requires to build works on a lake or river will depend on both the type of development, and whether or not the water body appears on the schedule.

Future regulations will set out which types of works will be considered minor, major or other. The “must apply for government approval” and “invite public comments” requirements are discussed more below.

Application for government approvals

For everything other than minor works on schedule-listed waters, and for major works on all navigable waters, a developer must apply for approval from the Ministry. However, unlike the pre-2012 rules, that doesn’t mean that an approval will be required.

On receiving an application, the Minister will make an initial decision about whether or not the work “may interfere with navigation.” If he or she “is of the opinion that a work … would not interfere with navigation” then no approval will be required.

Keep in mind that at this point, the Minister only has information about the proposed work from the person who wants to build it, the developer. There has been no notice to the public, no opportunity for anyone else to provide information about how the water body is or is not used for navigation or on the possible impacts of the project.

It is doubtful that this approach will allow the government to appropriately consider the cumulative impacts of multiple projects that individually do not affect navigation.

An approval is only required if the Minister decides on this initial review that the project may affect navigation, and only then will there be notice to the public and an opportunity for the Minister to hear from other stakeholders.

Inviting public comments

For projects that are not major (and not minor), and are not on schedule-listed water bodies, a developer has a choice whether to apply to the Minister for an approval (in which case the above rules apply) or to invite comments from the public on the proposed development. If a developer takes the latter approach:

- Notice of the proposed work must be given to the public. It’s not clear exactly how this will work, but it will likely involve posting information near the proposed work site, possibly posting it on a central registry and/or publishing it in a local newspaper. The notice will invite “interested persons” to comment to the owner in writing within 30 days.

- If the developer receives a comment from a member of the public that expresses a concern “relating to navigation,” the developer and the person who made the comment must attempt to resolve the concern within 45 days (or some other period specified by regulation).

- The person who made the comment may, within 15 days after that period, request that the Minister order the person to apply for an approval in respect of the work.

- The Minister may order the person to apply for an approval or may decide that no approval I required.

The Navigation Protection Act (post-2012) didn’t give concerned members of the public any recourse on non-schedule streams. So this “dispute resolution process” is an improvement – of sorts. But it is not restoration of lost legal protection for navigation.

Indeed, a member of the public concerned about work on a navigable stream will be swimming against the current. First, the individual needs to become aware of the project within a 30-day period. Since recreational (and even commercial) navigation is more limited in winter months (and therefore notices posted at the site might not be seen during those months), we can expect a lot of notices to be posted during winter months. Assuming an interested member of the public catches the notice anyway, they must then comment in writing, and then engage in up to 45 days of negotiations.

If the developer does not agree that the comments relate to navigation, then it’s quite possible that they may decide to go ahead with the development once the 30 day comment period ends, and it is not clear what recourse the member of the public would have.

This entire process makes protection of navigation entirely dependent on the watchful and vigilant member of the public. The government is no longer a proactive defender of public navigation, but an arbiter of a dispute between a developer and member of the public.

The new act does give the government additional powers to order the removal of things that obstruct navigation, including intervening when new information about an approved work comes to light. These powers may help to temper some of the above concerns.

In our view, however, this approach cannot be said to live up to the government’s commitment to restore lost legal protections for navigable waters.

Navigation, pipelines and transmission lines

In 2012, the elimination of government approvals for navigation on all but schedule-listed rivers and lakes was widely viewed as helping the construction of pipelines, which frequently cross many navigable waters. Bill C-69 offers the pipeline industry a different solution – exempting pipelines and transmission lines that are regulated by the new Canada Energy Regulator (CER, formerly the National Energy Board) from the Canadian Navigable Waters Act. Instead, the CER will have full authority to consider the impacts of the pipelines on navigation and to approve pipeline activities or transmission lines that affect navigation.

Conclusion

The federal government promised Canadians that the lost protections for navigable waters would be restored. In taking an approach which focuses narrowly on navigation (when Canadian environmental laws prior to 2012 required a broader environmental approach), and by allowing developers or the Minister (depending on the circumstances) to bypass the requirements for a transparent approval process, the Canadian Navigable Waters Act fails to deliver on this promise.

Top photo: Travel Manitoba via Flickr Creative Commons